GDP is no longer an accurate measure of economic progress. Here’s why – By Pushpam Kumar, Chief, Ecosystem Services Economics Unit

It is critically important we monitor societal progress and design responsive policies to 21s- century challenges, such as climate change, the marginalization of more than a billion people, resource depletion and emerging pollution-driven health crises. We need reliable metrics to know how we are performing on the yardsticks of our economy, sustainability and social harmony.

Unfortunately, our radar to track progress is far from satisfactory. Countries still use a 20th-century metric to measure wellbeing: Gross Domestic Product, or GDP.

GDP provides measurements of output, income and expenditure quite well, and these are needed to understand and devise fiscal and monetary policies. But this measure flatly fails when it comes to wellbeing. Its founder, Simon Kuznets, cautioned half a century ago that it is useful mainly in tracking income. More recently, other economists suggest knowing change in per capita wealth of all types is key to monitoring sustainability.

Hence growing international interest in a tool that still captures financial and produced capital, but also the skills in our workforce (human capital), the cohesion in our society (social capital) and the value of our environment (natural capital).

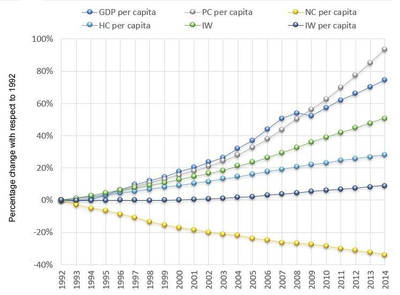

Work has advanced on some of these elements. The UN Environment Programme-led Inclusive Wealth Index shows the aggregation through accounting and shadow pricing of produced capital, natural capital and human capital for 140 countries. The global growth rate of wealth tracked by this index is much lower than growth in GDP. In fact, the 2018 data suggests natural capital declined for 140 countries for the period of 1992 to 2014.

Interestingly, many countries record GDP growth while they lose natural capital. One can see the trade-off among various types of capital, but the report clearly conveys that mixing income with wealth is bad economics and dangerous for sustainability measurement.

The Index’s findings include strong recommendations to help reach global sustainability targets, including the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Closely tracking countries’ productive bases is key, as a declining asset base implies a non-sustainable trajectory. Many of the assets critical for maintaining productive bases are either not priced or are priced at much lower levels than they should be. This is especially true for natural capital and human capital assets. Natural capital assets such as forests and water bodies have only been valued for the products they provide for the market, such as timber and fish. However, these ecosystems offer a much larger suite of services, such as water purification, water regulation and habitat provisioning for species, among many others. These are clearly valuable services.

The Inclusive Wealth Index also helps policy-makers prepare to negotiate for reductions in greenhouse gases as well as for compensations accruing from climate change. Further, past reports have shown conclusively how countries can become unsustainable in absolute terms when population growth is factored into the computation. Understanding the impact population growth has on productive bases is a critical variable that leaders should factor into policy-making.

So analytic progress has been made, but there is still need a need to bring all five elements of prosperity – financial produced, natural, human and social capital – into one framework.

A new Canadian report does this.

Canada’s Comprehensive Wealth project adds one number for evaluation and policy-making on top of GDP: a per capita sum of the five elements of prosperity. It draws on data from Statistics Canada – one of the finest statistical organizations in the world – which measures many elements of prosperity separately, to varying degrees of depth.

The report raises several red flags, most notably that Canadians’ comprehensive wealth only grew at an annual average rate of 0.2% from 1980 to 2015. In contrast, GDP grew at an annual average rate of 1.31% over the same period. In other words, the good GDP results of Canadians don’t have a strong foundation reflecting growth in earning potential, sustainable natural stocks, and diversified financial and produced capital.

There’s room for this study to grow in depth and breadth. The Canadian federal government should direct Statistics Canada to regularly report the country’s comprehensive wealth score.

People deserve an accurate sense of how well their economies are performing, with a view to long-term sustainability. GDP has and always will have valuable short-term insights, but to respond to 21st-century pressures we need a modern economic measure. Canada can lead the world as the first nation to adopt comprehensive wealth, making a commitment to the knowledge that empowers meaningful action.